by Florence Williams, Ph.D., Martha Hubertz, Ph.D., Joseph Lloyd, M.Ed., and Joseph Fauvel, B.A.

The issue of the multidimensionality of online learning has become even more important since the pandemic as we see an entire cohort of students enter college after having spent over a year fully online.

Overview

Once upon a time, there was a global movement that sent faculty at every level scrambling to get their courses into a digital modality. The importance of structure and sustainability were highlighted as learning and development practitioners saw workload increases not previously experienced. These were unprecedented times for both faculty and instructional designers. Meanwhile, in higher education, credit hours generated by online courses continued to increase year after year. As with face-to-face instruction, student engagement is critical for success in the online environment. Ideas of self-regulation, autonomy, and the gradual release of control espoused by adult learning theory came to the fore as new to online faculty recognized the complexity of the online modality.

Multidimensionality of Online Learning

The issue of the multidimensionality of online learning has become even more important since the pandemic as we see an entire cohort of students enter college after having spent over a year fully online. More than ever, these students have developed expectations of what a “good” online class should look like. Although there is consensus among faculty that the use of multimedia drives student learning and engagement, there is sparse research on their use at the higher education level. Danver (2015) explores the merits of using multimedia for content delivery and pedagogy in online education. Their review identifies the potential of multimedia for student learning and engagement. Mandernach (2009) suggests that “effective online multimedia is content-relevant and pedagogically intentional; as such, appropriately integrated multimedia components become valuable teaching tools for facilitating student learning” (p.1). Research into the efficacy of interactive content to assist students in building community, connecting to content, and remaining motivated and curious, found strong correlations between multimedia use and student success (Kebritchi et al., 2016; Pallof & Pratt, 2013; Rashid and Asghar, 2016).

A recent study by Hubertz and Vancampenhout (2022) suggests that student social and academic engagement are linked with academic achievement. They provide a stepwise implementation model for multimedia which serves as a successful practice opportunity for online educators. Hubertz et al. (2021) investigated the efficacy of multimedia use as a tool to drive learning and engagement. They noted that engaging students with multimedia, as with the Social Psychology image, is an excellent way to student success,

Aligning Multimedia Integration with UDL Principles

Kennette and Wilson (2019) reiterate the urban planning principles of maximizing access and minimizing barriers, which form the foundation of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). The three UDL principles; multiple means of representation, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of engagement taken together and interposed with curriculum development might lead to student persistence and therefore impact student success.

Multimedia such as graphic design within the UDL principle of multiple means of action and expression provides a proactive approach for student engagement where the learner can identify course expectations at a glance based on the graphics integrated into courseware.

Hubertz et al. (2021) in concert with the CDL Graphics guidelines (2016) highlight the importance of using illustrations, infographics, maps, graphs and charts, and photography for learning and engagement. A critical aspect of the UDL principle for students using assistive technology is consideration for accessibility support where Alt Text is included for each instance of digital graphics included in the course. Kennette and Wilson (2019) also suggest that students must synthesize information from multiple sources for future work.

As such, connecting to multiple representations of the same information (e.g., drawings, tables, and text) in learning environments might deepen their understanding of the concepts and provide a platform for the school-to-work connection.

Schools and universities make many efforts to increase student engagement and success. Course designers can use the UDL representation principle to advance that move with multimedia integration. While some schools may not have the resources to develop a full-on Monet (Hubertz et al, 2021), one strategy is to start by presenting basic course documents such as the syllabus, schedule, campus resources, and academic resources with icons within the online course.

Like what traffic signs do on a roadway, graphics in online course environments provide signals for upcoming content and changes to which students must pay attention as with these mummy action icons.

This principle was discussed in Fritzgerald’s multiple avenues to learning goals, where they speak to mitigating the challenges to student learning. Fitzgerald urges practitioners to implement UDL in frameworks to provide additional learner advances that incorporate the strategies that acknowledge student needs (p. 52). Thus, ensuring that students go through the course with minimal disruptions.

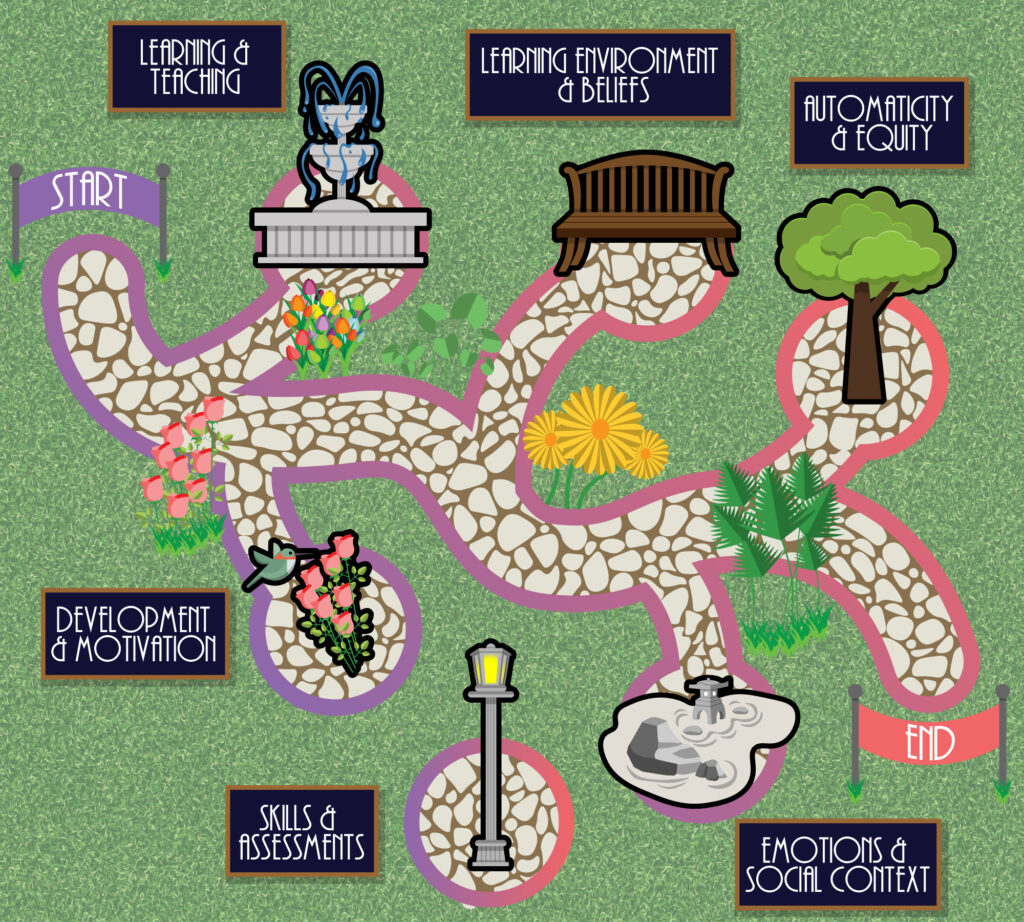

Implementing the UDL principle of multiple means of representation with multimedia integration provides success for those students who need support while simplifying the design for others who might benefit from these affordances in the online environment. Instructional designers and faculty have a unique opportunity to make the online classroom inclusive and support learner persistence. One caveat is to ensure that the graphics used are discipline relevant and used intentionally to improve accessibility, course aesthetics, and content quality, such as with a learning path image.

Equipping Faculty and Students to Succeed Online

The transfer of data remains relevant to teaching and learning regardless of the modality of transfer. Relying on this premise, instructional design principles must consider the techniques that can engender success online. The seminal work by Myer and Moreno presents the cognitive principles of multimedia learning, which establishes the use of multiple options for absorbing and retaining learning content (Myer & Moreno 1998; Meyer 2021). Designers can help faculty develop courses built on the principles of coherence and signaling to support motivation and self-determination. Adherence to the coherence principle, humans learn best when extraneous, distracting material is not included, requires that the multimedia included in the design should be related to the course content. Faculty members who want to add multimedia should therefore work with other professionals who can help to identify content that might prove distracting for the student.

In addition to excluding distractions, the signaling principle, also coded as contiguity, supports content and concept mapping that provide directions for learners as they navigate through the online course. This principle, humans learn best when they are shown exactly what to pay attention to on the screen, invites the course designer to identify the significant areas of the content for the learner. Faculty are encouraged to chunk the content in their design and to use multimedia to highlight important concepts and ideas matching learning objectives, content, and assessment.

Online learners consume content that offers the relatedness and recovery that reduce the stress they may bring to the learning process as espoused by Fritzgerald (2020). Students have the best opportunity for success online when they are presented with content that provides choice and maximizes their competence. Course design that considers coherence and signaling meets the UDL principle of multiple means of representation. Creating an organized course and offering choice for responses, feedback, and assignment completion meets the principle of multiple means of action and expression. Taken together, these combined theoretical frames are optimal avenues for online student and faculty success.

Online courses are dynamic and have moved from the yellowed notes pages that the erstwhile absent-minded professor used in the age-old movie about that ivy league university. Instead, the design of these courses aligned with the UDL principles have learners at the center (Fritzgerald, 2020; Meyer, 2021; Palloff & Pratt, 2013) with the multiple means of engagement. Engagement and learning are inextricably linked, and the connection cannot be unraveled.

Palloff and Pratt’s (2013) focus on online course development as an important medium for faculty and students bring the focus back to the collaborative nature of online course design. While the designer may not recruit student involvement at the outset, a reflective questioning approach to the design considers students’ learning needs and makes allowances for design feedback in delivery. The general advice for multimedia integration is to focus more on interactivity, rather than content transmission and delivery.

Conclusion

As we close this story, we can safely say they—students, faculty and learning and development practitioners—will only live happily ever after if consideration is given to the multimedia learning principles and the underlying UDL framework in their work. Course design must consider students as multifaceted beings as much as it views the online space as multidimensional.

References

Allen, L., Kiser, B., & Owens, M. (2013, March). Developing and refining the online course: Moving from ordinary to exemplary. In Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 2528-2533). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Danver, S. (Ed.) (2016). The SAGE encyclopedia of online education. (Vols. 1-3). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483318332

Fritzgerald, A. (2020). Antiracism and universal design for learning: Building expressways to success. CAST Professional Publishing.

Graphics Team (2013 – 2023). Images are original creative content of CDL Graphics. Center for Distributed Learning, University of Central Florida.

Hubertz, M., & Van Campenhout, R. (2022). Teaching and iterative improvement: the impact of instructor implementation of courseware on student outcomes. In IAFOR International Conference on Education–Hawaii.

Kennette, L. N., & Wilson, N. A. (2019). Universal Design for Learning (UDL): What is it and how do I implement it. Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal, 12(1), 1-6.

Lloyd. J., Hubertz, M., & Fauvel, J. (2022). A Full-On Monet! Taking Your Online Class to an 11! Presentation at the 2022 Florida Online Innovation Summit.

Mandernach, B. J. (2009). Effect of instructor-personalized multimedia in the online classroom. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(3).

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2021). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(1), 4-29.

Kumi-Yeboah, A., Kim, Y., Sallar, A. M., & Kiramba, L. K. (2020). Exploring the use of digital technologies from the perspective of diverse learners in online learning environments. Online Learning, 24(4), 42-63.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2013). Lessons from the virtual classroom. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 10(2), 93-96.

Rashid, T., & Asghar, H. M. (2016). Technology use, self-directed learning, student engagement and academic performance: Examining the interrelations. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 604-612.

Schrader, C., Reichelt, M., & Zander, S. (2018). The effect of the personalization principle on multimedia learning: the role of student individual interests as a predictor. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66, 1387-1397.