by Elizabeth J. Hubertz, Florence Williams, Martha Hubertz

Today’s educators can use Generation Z’s attitudes in the use of technology to support sustainability education and to create the informed and engaged smart city residents of tomorrow.

Abstract

The future of sustainability in an ever-urbanizing world may well be smart cities that make use of digital technology to direct services to the places, times, and people where they will be most effective. These cities need residents who can understand and will use these technological solutions. Today’s higher education students, members of Generation Z, support the use of technology to achieve a sustainable environment even as they are critical of its potential to widen the digital divide. Today’s educators can use Generation Z’s belief in the use of technology to support sustainability education and to create the informed and engaged smart city residents of tomorrow. To support this approach, we explore how instructional designers (IDs) and faculty can leverage Gen Z’s tech fluency to design learning experiences that prepare students for participation in smart cities.

Smart Cities

Smart cities are emerging as a solution for municipalities that want to improve infrastructure and public services, increase sustainable use of resources, and create vibrant and attractive urban communities. (Trinidade 2017). Through the use of Artificial Intelligence, the Internet of Things, and resource management, enhance public services, and reduce their environmental footprint. (Berry, 2021; Particle, 2021; Cesario, 2023).

Examples include:

- apps that provide real-time information about bus and train locations to dispatchers and riders or that guide cyclists through city traffic

- networked streetlights that adjust their brightness

- electricity meters that conserve power at times of high usage

- garbage cans fitted with vacuums to suck waste into underground storage, removing odors and pests from street level

(ASME 2020). Smart cities apply these same lessons of data to the social and economic realm to deliver better financial and social outcomes as well. (Shamsuzzoha 2021). Understanding the infrastructure and goals of smart cities allows ID professionals to align curriculum and learning technologies with real-world applications, fostering authentic learning experiences.

Successful smart cities require city residents who will be able to participate in and take advantage of technological solutions. Smart cities collect large amounts of data about their citizens giving rise to concerns about privacy and security of information that may undermine trust in the government. (Imam 2024). Technology anxiety plays a role as well since those who fear technology will be less likely to make use of it. (Lytras 2021) Without inclusive planning, the digital divide may limit access to information and communication (Kashef 2021).

Tech-Savvy Students

Smart city technology will only increase in the years to come. Today’s teenagers and young adults – Generation Z – will play an important role in the implementation of the concept of a smart city. In some ways, they are well equipped: Generation Z is the first generation to grow up in a world dominated by smartphones and digital technology, with 95% owning a smartphone and 25% having had one before age 10. They have the digital fluency to utilize smart city technologies and share the values of smart cities, supporting sustainability, use of technology, and social responsibility. They expect seamless personalized integration of digital information, and they are not overly impressed by technological novelty.

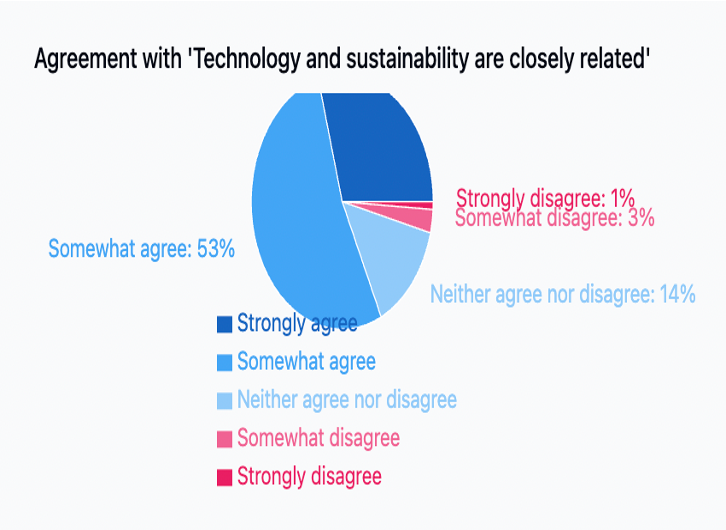

Based on a survey of nearly 1000 current students at a large R1 Hispanic Serving Institution, Generation Z believes strongly that sustainability and technology are closely related.

They view technology as an enabler of sustainability initiatives, with an emphasis on renewable energy, electric transport, and digital solutions. These insights can inform how IDs and faculty developers approach learner engagement, particularly when designing for values-driven, tech-fluent students

The identified attitudes were even more pronounced among minority-group members and younger members of the group. Minority members more strongly acknowledge the relationship between attitudes toward technology and sustainability and show a larger concern for equitable practices. Younger members, too, show more awareness of and support for sustainability, environmental justice, and climate. We encourage faculty and IDs to work together to use the findings to support inclusive design strategies and help tailor learning experiences that reflect the diverse values and priorities of today’s students. Even more importantly, while Generation Z students believe that technology can be used to support sustainability, they are not blind to its faults. They are critical of the potential for technology to exacerbate social inequities even as it solves environmental problems. IDs and faculty must collaborate to build on this critical awareness by incorporating opportunities for reflection, ethical analysis, and systems thinking into learning environments.

At the same time, the willingness of all Generation Z members to engage in sustainable behavior lags behind their enthusiasm. Sustainable behaviors like recycling, use of sustainable transportation, and water conservation have not fully taken root. This is as one would expect from the broader literature on the attitude-behavior gap, (Müller 2025), but offers room for increased practical education. We can bridge this gap together by designing experiential learning opportunities and behaviorally anchored activities that move students from awareness to action.

Smart Education, Smarter Cities.

A population engaged in and familiar with sustainability practices will make the smart city a success. While the cities themselves will have to translate communication and transportation advances into policies and practices, city residents must embrace the use of these new policies and practices for them to work well in the municipal space. (Lytras 2021). Cities will need to build trust among their residents, possibly through a phase-in of new programs and the use of currently accepted technologies first.

Today’s students understand the connections between technology and sustainability and that technology can be used to support sustainable outcomes. They trust technology, especially proven technologies like solar power and energy-efficient devices and will use it when it aligns with their goals. There is a need for cross-disciplinary collaboration to support smart city design thinking in education. IDs can therefore scaffold learning experiences that bridge the attitude-behavior gap by integrating experiential learning, simulations, and sustainability challenges into course design.

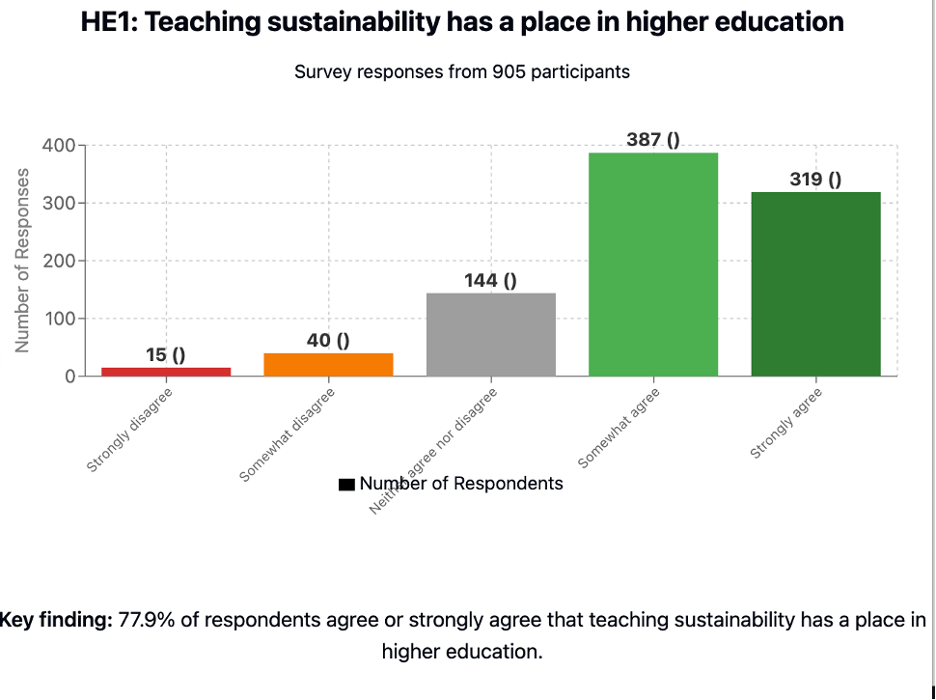

Today’s educators, in partnership with IDs, can leverage these Gen Z attitudes to include technological and sustainability themes and concepts in a variety of courses, including those outside the environmental science and policy realm. Educational programs should maintain a balance between fostering technological competence and developing awareness of implementation challenges and inclusiveness. Because there is a gap between environmental attitudes and sustainable practice, this should also be a focus of sustainable learning.

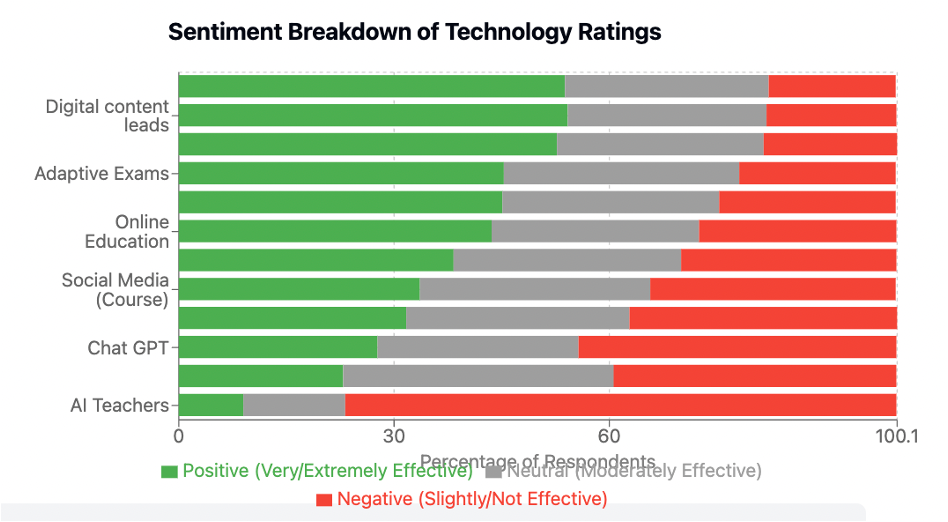

And faculty can use educational technology to teach. Just as they support technology when used in the service of environmental and equity goals, they support its use in education when they believe it helps them learn. Generation Z supports the use of digital content, adaptive exams, and online education. They do not want to eliminate the human factor in teaching, and they do not support the concept of AI teachers. When implementing technologies to support educational sustainability goals, educators can focus first on widely accepted tools like e-books, learning management systems, and video conferencing, which have broad support.

Key Insights:

- Top Technologies: E-books, learning management systems, and video conferencing tools are perceived by students as most effective for education sustainability.

- •AI Adoption: While AI-enhanced books are relatively well-received, standalone AI teachers face significant skepticism (76.8% negative ratings).

- •Digital Resources: Technologies that digitize traditional educational resources (books, course materials) rank highest.

- •Social Learning: Social media platforms for education show moderate effectiveness ratings, with slightly higher support for course engagement than peer interaction. This is most likely due to how these platforms are used by faculty.

Summary

Generation Z will bring smart cities to life and make them work for a more sustainable and equitable world. Their technological optimism, coupled with a critical understanding of technology’s potential for inequitable outcomes, makes them well-positioned to navigate the complexities of smart city implementation. Smart cities need residents who are technologically literate, who appreciate technological innovation, and who will adopt technological solutions for urban living.

As new technologies develop, city residents will have to adapt to these new formats and uses in order for smart cities to continue their success. Faculty and IDs are uniquely positioned to translate Gen Z’s digital fluency and sustainability values into impactful learning experiences that prepare students for smart city citizenship. With this collaboration, educators can focus on designing frameworks to address these intersections of technology attitudes, sustainability concerns, and demographic factors while supporting the development of residents equipped to implement smart technology in an effective manner.

References

Berry, I. 10 ways AI can be used in Smart Cities. AI Magazine (Nov. 2021). https://aimagazine.com/top10/10-ways-ai-can-be-used-smart-cities.

Cesario, E. Big data analytics and smart cities: applications, challenges, and opportunities. Frontiers in Big Data.1-13 (May 2023).

Inam, M.L: Top 10 disadvantages of smart cities. Minnovation Technologies. (2024) https://minnovation.com.au/smart-cities-2/disadvantages-of-smart-cities-potential-challenges-and-concerns/.

Kashef, M., Visvizi, A., Troisi, O.: Smart city as smart service system: human computer interaction and smart city surveillance systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 124 106923 (2021).

Lytras, M. Miltiadis, Visvizi, A., Chopdar, P. K., Sarirete, A., Alhalabi, W. Information Management in Smart Cities: Turning end users’ views into multi-item scale development, validation, and policy-making recommendations. Int’l J. Infor. Mgmt. 56,102146 (2021).

Müller, A., Bács, Z., Fenyves, V., Kovács, S., Lengyel, A., & Bácsné, E.B.: Demographic influences on environmental attitudes and actions: An analysis of the attitude-behavior gap. Geo. Tour. Geosites. 60, 1028-40 (2025).

Particle. Three ways to start building a connected infrastructure. Smart City Business p.10-11 (Dec. 2021). https://issuu.com/psi-media/docs/smart_city_business_december_2021?fr=sNDQzNzQ0NzUyNTg

Shamsuzzoha, A, Nieminen, J.,Piya, S., Rutledge, K. Smart city for sustainable environment: A comparison of participatory strategies from Helsinki, Singapore and London. Cities. 114,103194 (2021).

Trinidade, E.P., Hinnig, M.P., da Costa, E.M. Marques, J.S. Bastos R.C., Ygitcanlar, T.: Sustainable development of smart cities: a systematic review of the literature, J. Open Inno. Technol. Mark. Complex. 3, 1-14 (2017).

Williams, F.W., Hubertz, M.J., Hubertz, E.J.: Building Sustainable Smart Cities on the Hopes of Tech-Savvy Students. Human-Computer Interaction: HCI in Business, Government and Organizations, Held as Part of the 27th HCI International Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden, Proceedings (2025).

Authors

Elizabeth J. Hubertz, ejhubertz@wustl.edu, Professor of Practice, Director, Interdisciplinary Environmental Clinic, Washington University School of Law

Florence Williams, Faculty Instructional Designer, Center for Distributed Learning, Division of Digital Learning, University of Central Florida

Martha Hubertz, Associate Lecturer, College of Sciences, Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida