by Marti Snyder, Alfreda Francis

“Wenger, McDermott, and Snyder (2002) defined communities of practice (CoPs) as groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis…” (p. 4). Virtual CoPs (vCoP) are those that leverage digital technologies to support the CoP’s mission and facilitate community activities.

Overview

MAKO Commons is a vCoP for faculty of Nova Southeastern University. The design decisions that were made to build the CoP, including the establishment of purpose, activities and tools, stewardship, and next steps were guided by Wenger, White, and Smith’s (2009) framework and action notebook.

Different Types of CoPs

Within the context of higher education and faculty professional development, CoPs have been used to support formal and informal learning. When discussing CoPs, it is important to identify the specific dimension of CoP being referenced, as the theory has evolved over the years. The original theory emphasized the apprenticeship model whereby novices become competent in a particular domain and move from the periphery of the community to taking on a more central role through legitimate peripheral participation (Buckley, Steinert, Regehr & Nimmon, 2020, p. 764). Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (2015) described a more open CoP concept of a social body of knowledge and “knowledgeability” that acknowledges people may participate in multiple communities of practice. They may not be competent in each area of practice, but rather broadly knowledgeable about them and the communities’ applications to their practice. MAKO Commons follows this more open CoP concept.

Following is a description of each step and how we used it to design MAKO Commons.

Preamble: The action notebook begins with a preamble focused on the role of a tech steward. As the director and assistant director of faculty professional development, we took on the roles of tech stewards for the MAKO Commons. The following five questions helped us reflect on our roles. This reflection helped us think through our rationale for creating the vCoP, think carefully about our time and resources, and determine how to move forward in the design.

- Why are you doing this? What do you expect?

- What is your background and how does it affect your bias?

- How much energy and time do you have for stewarding?

- What gives you the legitimacy to play this role?

- Who else is interested and could help you by offering resources?

We determined that we wanted to start simple and use an agile and grassroots approach to building the vCoP. We wanted to “let it evolve,” so that ownership could be felt and shared by our members. The preamble helped us to define the goal and mission of the MAKO Commons as follows:

Our Goal

Our goal is to foster and sustain a community of NSU faculty that advances the learning of all members.

Mission Statement

The MAKO Commons is a virtual community of practice (vCoP) designed to connect faculty across NSU so that we can share ideas, information, and resources related to research and practice in teaching and learning. We strive to engage in collaborative learning within an environment of shared authority, trust, and mutual respect. We hope through the MAKO Commons to Make All Knowledge Open so that we can learn from each other and strengthen our institutional capacity for effective teaching and learning.

Connection to NSU’s Mission

Through an open sharing of knowledge, we hope to achieve NSU’s mission to “foster academic excellence, intellectual inquiry, leadership, research, and commitment to community through engagement of students and faculty members in a dynamic, life-long learning environment.”

Step 1: Understand Your Community

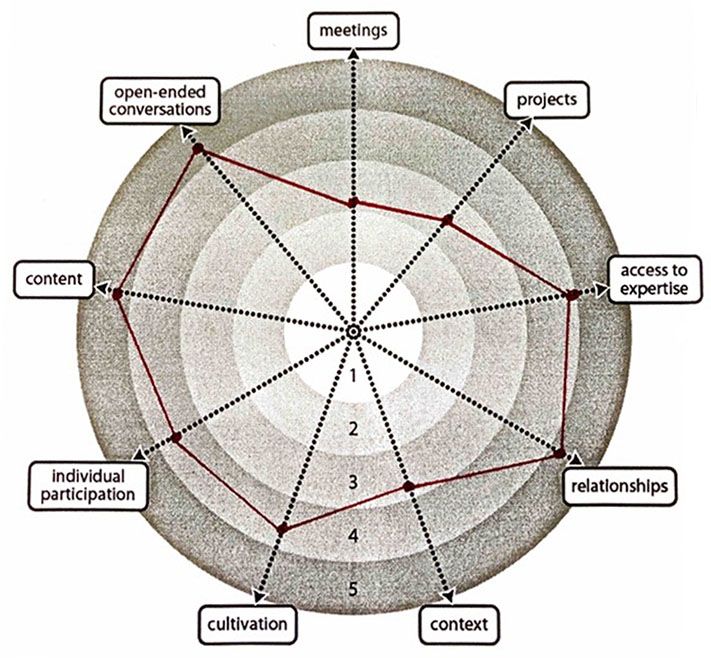

This step helped us think about where the vCoP was in its lifecycle (i.e., just forming) and the constitution of the community in terms of diversity and openness. While we designated this vCoP for faculty, we defined faculty broadly to include anyone at our university who is involved in teaching students, including full-time and part-time faculty, adjunct faculty, instructors, administration, and staff. We completed a spider diagram (See Figure 1) to create an orientation profile, which helped us to determine our platform and what to include.

Note: Each orientation was rated from 0=irrelevant to 5=very important. This visual diagram helped us to understand what we valued in our community, which in turn helped us to select the tools and activities we needed to include. For example, given open-ended conversations, content, and individual participation, we made the online discussion forum a focal point so that community members could interact, share ideas, and offer resources.

The output of this step helped us to define initial community activities:

- Providing opportunities for communication, collaboration, and interaction among all members

- Encouraging the sharing of information, knowledge, and experiences

- Supporting the development of teaching and learning expertise through research and practice

Step 2: Provide Technology

This step focused on the selection of technology to use to support the vCoP. Considering our goals, resources, and constraints, we selected to house MAKO Commons on Canvas, our university’s learning management system. All our faculty are familiar with Canvas, so there was not a learning curve to participate in the Commons. In addition, it is a private network behind the firewall. In addition to having asynchronous activities, we discussed scheduling a few synchronous meetings, which we would coordinate through Zoom until we are able to safely meet on campus. Although Canvas might meet our immediate needs, we discussed the limitations, such as not having a robust, searchable repository of content and the possibility to extend our vCoP beyond our institution.

Step 3: Stewarding Technology Use

This step helped us think through many of the logistics involved in developing the vCoP such as how many members to have, how to onboard them, who will assist in stewarding the vCoP, expectations and time commitment of faculty, and how often we should communicate with our community members.

Where We Are Now

We announced an invitation to MAKO Commons through our university’s faculty development newsletter and recruited 40 members representing colleges and offices across the university and regional campuses. We are using an agile and participatory approach to development.

References

Buckley, H., Steinert, Y., Regehr, G. and Nimmon, L. (2019). When I say…community of practice. Medical Education, 53, 763-765.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R. & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. Boston, MA. Harvard Business School Press.

Wenger-Trayner, E. & Wenger-Trayner-B. (2015). Learning in a landscape of practice framework. In Wenger, E., Fenton, M., Hutchinson, S., Kubiak, C. & Wenger, B. (Eds.). Learning in landscapes of practice. New York: Ed. British Library, 246-257.

Wenger, E., White, N. & Smith, J.D. (2009). Digital habitats: Stewarding technology for communities. Portland, OR: CPsquare.

Authors

Martha (Marti) Snyder, Ph.D., PMP, SPHR, Director of Faculty Professional Development, Learning and Educational Center, Office of Academic Affairs, Nova Southeastern University; Professor, Fischler College of Education and School of Criminal Justice, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Alfreda Francis, Assistant Director, Learning and Educational Center, Office of Academic Affairs, Nova Southeastern University