Author(s): Dr. Amanda Major, Sue Bauer

Editor: Dr. Shelly Wyatt

Dear ADDIE,

I am an instructional designer (ID) at a large university who works on a large team of instructional designers (15+); we collaborative on a variety of projects that I mostly enjoy. For example, we may work with our faculty and several support teams to (re)design faculty courses, collaborate with other instructional designers to launch new faculty development programs, and even contribute to online campus initiatives that need immediate attention. Many of my fellow IDs possess expertise in instructional design and online instruction but do not necessarily have project management experience. In general, we find it challenging to complete projects in a timely and efficient way. We have found that those with project management skills appear to have an easier time defining their projects, facilitating productive meetings, and submitting deliverables on time. What resources or guidance can you provide to help us adopt a more project management (PM) mindset?

Thanks,

Leader of the Band

Dear Band Leader,

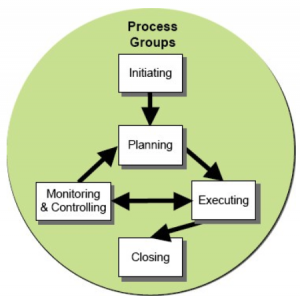

As a time-limited endeavor, projects have a lifecycle. Those with a PM background move through the processes that comprise a lifecycle for facilitating productivity:

- Initiating

- Planning

- Monitoring & Controlling

- Executing

- Closing

By DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS Office of Information and Technology (Project Management Guide) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

To move through these processes, the quick establishment of credibility as well as trust is essential. This trust ultimately creates the vital bond that brings together stakeholder management, team facilitation, management support, and meeting clients’ expectations. Defining clients’ expectations and sustaining a project in any environment is challenging–and in large universities these tasks represent an even bigger challenge! The complexity lies in that clients are difficult to define. They seem more like a group of stakeholders (or those who are affected by the project) who do not directly compensate us for our efforts than actual clients.

These client-like group of stakeholders may be the state board of governors, your associate vice provost, department heads, a group of faculty members, a faculty member with whom you’ve worked for years, or students. Clients are so important, as success factors of a project are based on their perceptions and consensus. Their perceptions of quality and when the project must be completed definitely counts!

The role of the instructional designer varies from institution to institution. Some IDs perform project management roles in their work: some principal investigators conduct research; faculty development managers guide the development of applications (or tech tools); some professionals design, develop, and deliver professional development; and some organizational development specialists guide online program rollouts and campus initiatives. Even if an ID does not lead on a specific project, they utilize project management practices and techniques to contribute as a team member.

Even if your team members have a background in management, this background may not be enough to successfully structure projects. It takes a strong skill-set. This skill-set differs from the competencies needed to manage ongoing operations, like consultations with faculty members or recurring training. Managing projects may require establishing relationships with a new set of stakeholders. It takes additional effort to create goals and facilitate the team’s productivity. You have to be a jack-of-all-trades because of the many different specialization considerations needed, as follows:

- Resource Management

- Integration Management

- Time Management

- Scope Management

- Quality Management

- Stakeholder Management

- Communications Management

- Risk and Budget Management (depending on the project).

These are basic elements of project management according to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMI, 2017). Instructional designers can use these in their leadership or contribution on a project.

Here are some tools, strategies, practices, and techniques that may assist with guiding successful project completion.

Project Management Infographics

Project Management Terminology

Online Project Management—Infographic

Agile Project Management—Infographic for Short-Term Projects

Integration Management Tools

Integration management is a Knowledge Area covering the coordinate of the core project life cycle.

Google Suite

Templated Files for Project Management

George Mason University’s Project Management Office Templates

Free Project Management Templates from Project Management Docs

General Resources

The Role of an Instructional Designer as a Project Manager by Marina Arshavskiy, March 25, 2014

SkillQ Advisor—Project Management for Instructional Designers Video

OLC Project Management for Instructional Designers Course

Thanks for your question. I hope that these resources come handy. Do you have some project management resources, strategies, or tips you’d like to share? Please share your thoughts with our TOPkit community on LinkedIn!