Author and Editor: Dr. Denise Lowe, University of Central Florida

Dear ADDIE,

Thanks for your responses to the issues we all share in Instructional Design. I’m an ID at FAU and work with some amazing faculty. Of course, the faculty member has the ultimate say in their course. One question that I have been ‘pondering’ has to do with the weighted percentages many faculty like to use. I have been wondering if there is an effective way to explain that concept to students. At times I am unclear about the grouping of assignments and the ultimate value of specific assignments. I imagine that students are also somewhat muddled by this concept. Thanks in advance for any clarification you can provide, both for me and to share with others.

Signed,

Muddled and Confused

Dear Muddled,

What a great question for this forum! I’m sure many instructional designers – and even faculty new to teaching – have wondered this same thing. Some faculty choose to use a simple point system for grading of assignments that may or may not include extra credit points as well. In this case, there is a maximum number of points for all assignments given in a course. The total points earned for these assignments equals a specific letter grade. Very simple to understand and implement – so why would an instructor elect to use a weighted system in which certain groups or individual assignments have a higher percentage weight in the course than others? It can, indeed, be confusing for students to understand and calculate where they stand in a course at any given time.

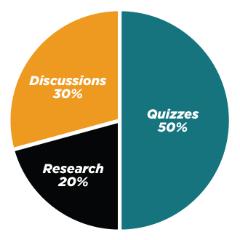

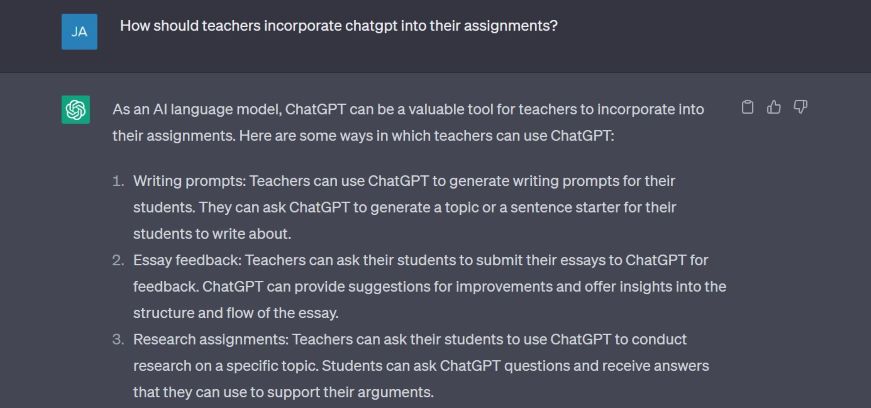

First, let’s understand that “grouping” assignments can be used for simple point or weighted grading systems. In simple point grading schemes, this grouping places similar assignments together for ease of viewing and course planning. In a “weighted” grading scheme, however, the assignment groups reflect specific percentages of the total course grade, and those percentages equal 100%. When the overall points for a specific assignment group are calculated, they are multiplied by the percentage attached to that group. The final grade is determined by adding the group percentage grades to obtain a total. The great thing is that all learning management systems work well with weighted systems. Canvas specifically has a “What-if” function that allows students to see what their final grade would be in they earned various grades on remaining assignments (Barrett-Fox, 2023).

The learning management system will determine the overall course grade by performing this calculation:

Final Grade = (average Research grade) x 20% + (average Discussion grade) x 30% + (average Quiz grade) x 50%

Many proponents of weighted assignments claim there are several advantages to this system of grading. According to CTLD Support at Metropolitan State University of Denver (2021), making the assignment points equal a specific number is unnecessary; points do not need to be shuffled when assignment changes occur; and weighting ensures that more in-depth assignments will be worth more than multiple small assignments. The instructor can determine and reflect which assignments are of greater value, which provides them greater flexibility. Instructors may also be able to view patterns of student grades within the gradebook subcategories for specific types of assignments to allow for tutoring or intervention – while students can see their own individual activity patterns for improving their academic skills (Salt Lake Community College, 2021). The best part is that you don’t need to worry about the math and all those potentially moving points!

Critics of this grading method, however, argue that students may have less incentive to do well at coursework that counts less towards the overall course grade. I would argue that this could occur using either grading scheme, as students may still be less likely to expend their energy on lower-point activities. Franke (2018) concludes that weighting of assignments, especially final assignments, should be done in a critical and intentional manner since uncritical assignment weighting can discount student learning that has occurred throughout the course, not just at the end.

Considering the pros and cons for using a weighted grading scheme, here are some best practices for implementation (CTLD, 2021):

- Instructors should thoroughly explain the system to their students, using graphics as visual references.

- Important assignment groups should be weighted more heavily than less assignment groups.

- All assignment groups should total 100% – unless extra credit is provided.

- Individual assignments should still be worth the number of points that make sense, based on the grading criteria used.

- With each assignment group, points are still relevant when compared to one another. For example, a 60-point discussion assignment will have greater impact on the final grade than a 20-point discussion assignment.

For an example of how to share the weighted assignment grading scheme with your students, you might want to point them to this video for How Weighted Grades Work (Warner, 2016). The video provides an easy-to-understand instructional format with examples to demonstrate weighting grades in practice. Another simple instructional video is How Do Weighted Grades Work (McCrady, 2021) – similar title, but a different presenter.

What other ideas regarding the use of assignment grouping and weighting – or other grade book strategies – have you applied or are exploring at your higher education institution? Please share your thoughts with our TOPkit community on LinkedIn!

References

Barrett-Fox, R. (2023, August). Lighten your load: Weight grades. Rebecca Barrett-Fox.https://anygoodthing.com/2020/10/15/lighten-your-load-weight-grades/

Franke, M. (2018). Final exam weighting as part of course design. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 6(1), 91-103. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.6.1.9

McCrady, V. [Victoria McCrady]. (2021, January 19). How do weighted grades work [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L16_SgnBxcw

Metropolitan State University of Denver, Center for Teaching, Learning and Design (2021, April 19). Weighted Grading. https://ready.msudenver.edu/canvas-spotlight/weighted-grading/

Salt Lake Community College. (2021, August 3). What are the benefits of weighting assignment groups in Canvas? SLCC Knowledge Base. https://slcconline.helpdocs.com/instructional-best-practices/what-are-the-benefits-of-weighting-assignment-groups-in-canvas

TOP HAT. (nd). Weighted Grades. https://tophat.com/glossary/w/weighted-grades/

Warner, B. [Brent Warner]. (2016, July 29). How weighted grades work [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1WJT-ckF6PU

!["Module-based objectives...can serve as a kind of checklist that spells out what [students] should know and be able to do..." (Adelphi University, 2021)](https://topkit.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/blackbubble_issue-24.jpg)